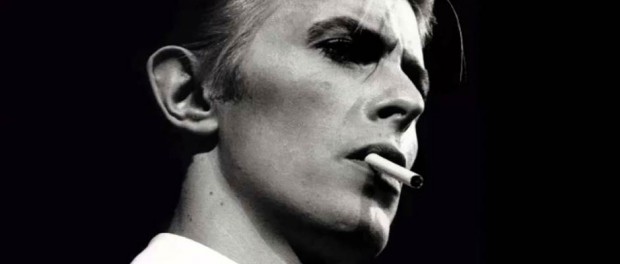

David Bowie: an appreciation

“It ain’t easy to get to heaven when you’re going down”

A life of surprises – and an exit to match. No more David Bowie: as cruel a rug-pull as fate could have had up its careworn sleeve. And, as with much of the staging and acute pageantry of his life, timed with a dutiful eye for presentation. That photo taken by Iman, on the day he released his final album (the brave, unique and maddening Blackstar), and just two days before he left us, is a wonder: no one could make a grey suit look less like a grey suit than Bowie, and no one had that smile. The end in sight and there he is, aping while the missus sneaks a picture. Chomping down on life even as it finally out-ran him.

In 2016, we’re hot-wired to be hyper-aware, to be minor contributors to an on-standby, ersatz community. And our brave new world has watered down those ‘Where were you when..?’ moments to little more than momentary flickers: watershed events made immediately global by the momentum of mere ones and zeroes. Where were you? Where was I? A desk. 7AM. A phone. Twitter. The news. The news. First the blunt force of those words and that reality, then the doubts, the nervous questioning and then, finally, confirmation. The reality of the situation becoming a dull thud, an ugly act of violence compelling disbelieving eyes to take in the dire, inarguable truth. Where were you? I was somewhere, nowhere, everywhere. The phone rang. And it rang.

When Bowie sauntered out of exile with 2013’s ‘Where Are We Know?’ (another grim January morning, pulling over for petrol while Chris Evans – don’t ask – revealed the news, now that you ask), we’d all but given up hope. What a strange shift that was: a gradual desire that began from so little, and built and spread. Few could have actually listed his most recent works at that time but, after the London Olympics of 2012, where we desperately poked around the back of the cultural store cupboard, seeing what we had left to wave in the world’s face, Bowie became something of a fixation. But he had steadfastly resisted artistic director Danny Boyle’s advances and so, with The Beatles no longer an option and ABBA still frustratingly Swedish, we settled for The Who, Arctic Monkeys and Paul McCartney (the go-to guy for pretty much an opening or closing anything of late.) The gap felt huge. We needed the Dame.

But Bowie, having managed to outwit the world by recording an album in secret, was still setting the parameters of his own wayward genius. The Next Day, released shortly afterwards, confounded and delighted. His first album in a decade and his best in at least twice as long, this was faith repaid with interest. At the time, I’d Googled “David Bowie” for a feature and Google had helpfully auto-completed with “health”, “discography” and “dying.” I recoiled. Bowie was back. But was he, really? On whose terms? And for how long?

Cancer. Of course cancer. Now that, you could have predicted. Not because of the fags so much but because it was always going to take something as vast, elemental and unforgiving as cancer to take him down. You could imagine him having the panache to be eaten by a shark but he’d have been embarrassed to have gone out being knocked over by a bus, double decker or not. A grand exit or nothing. Until you’ve had your life and your family subsumed by it, cancer exists as a grey, chill threat: looming. Its reality is merciless. Consumed by the cruellest disease, you suspect Bowie battled it like a centurion and with, surely, a haughty disregard. Fuck you, cancer. D’you know who I am?

My favourite Bowie things: ‘Kooks’, with the sweetest hook he’d pen, and a fade-out that dares arrive two minutes too soon; Live Aid, where he redefined ‘Heroes’, snuck in ‘TVC15’ and generally beamed through his set like he’d been called upon to save the day; the vocal melody (“See these eyes so green…”) on the verse of ‘Cat People’; the pinpoint poetry that overtures ‘Oh! You Pretty Things’; how he barely ghosts through “Will you see that I’m scared and I’m lonely?” on ‘Sweet Thing’; the hair, of course (always an exhibition but at its most magnificent when he’d, you know, let it go a bit); ‘I Can’t Read’ from the unfairly (or, to be fair, fairly) maligned Tin Machine; ‘Little Drummer Boy’; 2003’s excellent Reality; all of the Berlin instrumentals; Ronson’s peerless guitar on ‘Time’. Hmmm. Ask me tomorrow and you’ll get a different list entirely.

His eventual retreat and his preference for silence in recent years was more than just ‘let the music do the talking’ modesty. What more did he have to say? And, more crucially, who had the questions? Bowie, an artist whose self-referencing defined much of his deeper oeuvre, was never one for self-aggrandisement. This is the man who rejected a knighthood: he didn’t need our pedestals.

And he’s gone: closer to that golden dawn, and leaving behind more treasure than it is surely possible to house. One day they’ll all be gone and we’ll blink as if time had played a terrible trick. Dylan. Cohen. Joni. We should get ready. Kidding ourselves they’re invincible, this magical elite, is misguided short-termism but what choice do we have? We feed off them and they keep us alive. Bowie is gone and we are all kinds of bereft. As the huge – and, for once, dignified and impeccably observed – outpouring of grief for his passing has proved, it’s not so much that we needed him: his excellent recent work stands on its own merits and not as a valiant protection against the broader humdrum. No, we’re simply stunned, hurt, deeply confused. We hadn’t planned for this at all. How did we end up forming such a deep bond with the alleged chameleon, an artist – through early characterisation or his later preference for privacy – so defiantly unknowable?

Is he really gone? He’s gone. Leaving us more aware than ever of the warm impermanence of, well, everything, and the immeasurable magic we create when we dare to listen, dare to learn, cast aside what we think we know. Hearts and minds. Truth and beauty. Inextinguishable vision. We loved him as much as we dared and as much as he would allow. Legend? With his parting breath, the word loses all meaning. With Bowie gone, here, writ large, is blinding proof of Thomas Mann’s assertion that a man’s dying is more the survivor’s affair than his own.