Much Too Much: the Curse of the Double Album

The history of recorded music has been one of continuous expansion of the capacity of the medium. The world’s first million-selling record, ‘Vesti La Giubba’ as sung by Enrico Caruso, appeared on a state-of-the-art 78 rpm three minute-per-side shellac record in 1904. Expanding disc size from ten to twelve inches bumped playing time to five minutes and this would remain the upper limit for four decades.

While limited, this historical point of origin created enduring expectations of how long a normal ‘pop song’ would last. The replacement of shellac by vinyl in the late forties saw seven inch 45rpm singles created as the direct replacement for the gramophone record, while the twelve inch 33rpm long-playing record, the LP, with its 40 minute running time replaced the weighty multi-disc boxsets previously used to capture longer opera and classical performances. Very rapidly, however, the potential for artists to create entire suites of music – the album as we know it today – led to burgeoning ambitions built on the back of the format’s opportunities – and restrictions. The 40 minute album became the standard model yet, only a decade-and-a-half after the introduction of the LP, Bob Dylan one-upped his competitors with the 73 minute long Blonde On Blonde album of 1966, sparking the arrival of the double LP into the world of pop and rock.

The compact disc was the next paradigm shift and, again, its capacity would impact upon the concept of what an album could be. While experimental CD formats had crammed up to two-and-a-half hours onto a single disc, it was the 74 minute CD that made it to market (rumours abound that the length related to the performance time of certain classical concertos). With every release now appearing on a format with the capacity to breach the 40 minute mark, double LP length albums could became the standard rather than the exception.

Musicians – instead of creating, roughly, eight to ten songs for a release – now found themselves nudging song lengths up and/or needing to find twelve to fourteen songs each time. This posed a problem. Scaling upward – think Sonic Youth’s Daydream Nation or Nine Inch Nails’ The Downward Spiral – worked in skilled hands, but often albums pushing toward or over the hour could become wearisome endurance tests overloaded with filler tracks, with sound-alike songs, and with a lack of diversity either vocally, thematically or instrumentally. As the Nineties wore on, the traditional album became a less and less coherent concept, with ever less consumer loyalty, thus paving the way for the open-endedness of the Internet-era. Even so, most performers desiring critical acclaim and artistic credibility continued to confine themselves to sub-one hour lengths – except where bold intent intervened.

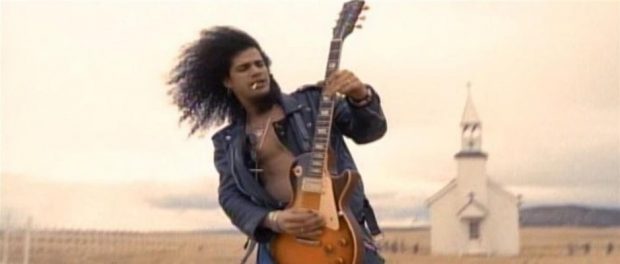

Unfortunately pride and ambition can become simple hubris and the Nineties saw the arrival of the double CD length album: the most persistently awful decision an artist’s ego can land upon. Guns ‘n’ Roses famously released Use Your Illusion I and II on the same day in 1991 – but this wasn’t strictly speaking a double album. The two volumes were structured as standalone releases and could be treated as such: there was no attempt to have one overarching experience running throughout this massive release and, being fair, there was sufficient diversity across the two packages that even the odd misstep, or the much-lamented move away from the sound of their debut, couldn’t dim its commercial success.

When seperate albums are packaged together, it is rarely intended to make the same statement as an uber-length ‘album’. The Weeknd re-released his three early mixtapes as Trilogy, a three CD boxset and, though linked by theme and sound, there was no intention for it to stand as a single release – it was just convenience. The same could be said of the trend for adding a bonus disc of one kind or another to a release: the bonus disc is explicitly an ‘extra’ loaded with material designed to stand alongside but never overshadow the ‘album’ – there’s a clear distinction between one concept and the other.

The double CD album first became a real problem in the world of hip hop. Whether through one-upmanship, a desire to gain easy publicity, cocaine or simply an inability to self-edit, Tupac’s All Eyez On Me was an overlong and wearying experience. Recorded and issued at incredible pace, the record’s best songs were those – like Dr Dre’s ‘California Love’ – that had benefitted from a longer gestation. Though containing plenty of moments where a fired-up Pac sounded inspired, these were spaced out with other songs featuring predictable beats and songs saying nothing new (the vast flood of posthumous recordings – including half-a-dozen double CD releases – have long since drowned Pac’s legacy in mush.) The Notorious B.I.G., by contrast, took a more methodical approach to his magnum opus Life After Death, resulting in a double CD album that, though still overlong, was packed with hits and guest verses of genuine quality that it remains a classic album. It helped that The Notorious B.I.G. was so focused on lyric-writing as a skill deserving of time and finesse: after his death there weren’t even enough stray verses left to make even a single posthumous disc without most of the runtime being taken up by guest artists – the only lyrics he laid down in studio were those he had crafted to perfection.

With that one notable exception, the hip hop double album has always proved a bad plan for legend status. Wu-Tang Clan, after a remarkable run of albums by the various group members, made their full return with 1997’s Wu-Tang Forever which – while benefitting from the presence of such a large group of premier quality vocalists, flagged as song-followed-song in a never-ending torrent that made many seem undistinguished or repetitive. Nelly tried the GnR sidestep by releasing Suit and Sweat simultaneously with each intended to showcase a separate aspect of his sound, yet each album suffered from a surfeit of unexceptional songs – a single album, culling the best of both records, would have been a better showcase. Nas, another iconic figure, gave the double album a shot but Street’s Disciple fell well short of his best work: again, smothering his best songs of the moment with shovel-after-shovel of less interesting work simply deadened the overall impact of even the album’s peaks – but, perhaps, after years of being told nothing he did was as good as Illmatic he had nothing to lose by trying.

The sin of an overlong album is often that it feels like a dumping ground from an artist disinterested in the value that can come from editing: it’s as if it marks the moment when an artist comes to feel their shit is gold and the public will buy whatever they dole out. Prince’s Emancipation album of 1996 did little to enhance his credentials, to rescue him from the wobble in his popularity, or to mark a significant artistic step forward. It felt like there was no purpose to it except to make people say “this is the first triple LP R&B studio album ever released.” Compilations and greatest hits sets had shown that a ‘jukebox-style’ listening experience could work but such releases make no effort to be a statement of any coherence, order or message. Seeing one of the most innovative artists of the previous decade-and-a-half spoon out so much music, but much of it empty, was disheartening.

In the world of rock, the double album often feels like the “What do we do now?” move where a band in search of something they haven’t already done decides that gigantism is an answer. Foo Fighters did it on the In Your Honour set: a disc of rock material then a disc of gentler ballads. Unfortunately the release caught Dave Grohl and co. at the moment where earlier promise and excitement had finally died away and what was left was a workaday stadium alt-rock band chugging away endlessly at their song production line. It’s noticeable that Foo Fighters’ Greatest Hits record would feature only one song from their grandest release. Metallica – a band who so often define overreaching – had released the Load / Re-Load records in 1996-1997 then dabbled with the two disc Garage, Inc. and S&M releases back around the millennium but took until 2016 to attempt a bona fide double album: Hardwired…To Self Destruct. The fact only one song clocks in under five-and-a-half minutes explains why 12 songs take 77 ½ minutes but still doesn’t excuse the serious fall-off in energy on the second disc. It also doesn’t excuse them for not realising that they had written roughly eight of their best songs in years, and that sticking to 40 minutes would have been a far more shattering experience than the listener pummelling effort they chose to release.

Trent Reznor’s Nine Inch Nails took a credible shot at the double CD album with 1999’s The Fragile – a record that Reznor has made very clear was heavily influenced by his spiralling drug issues. An excellent, diverse and rewarding first disc is followed by a second disc that simply doubled down on the sounds, moods, themes and instrumental approaches that laced the first disc. It begged the question why leaving a few months between the two discs wouldn’t have made each resonate more powerfully. Reznor clearly feels differently, having moved onto blurt out the ambient repetitiveness of the two CD Ghosts I-IV release (apparently four EP length releases all released at once but who can tell any difference?); then to hammer the same trope home with the three disc soundtrack to The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo then the two disc soundtrack to Gone, Girl; then this year’s expansion of The Fragile alongside a brand new album of ‘deviations’ on The Fragile. You’re watching a hugely talented musician, create some intriguing music then force feed you every last scrap they’ve created until you’re fit to burst and numb to the experience.

So does the double CD album ever work? It requires something truly special. Ultimately, a pop artist writing in the mode of songs in the three to five minute bracket doesn’t derive any benefit from putting over 20 such songs on a release – except in terms of covering market demographics (a trend that despoiled a huge number of albums in the late Nineties and early 2000s.) Likewise, even bands dealing in lengthy songs and ambient mood can become tiring if they’re not able to juggle the need for a classic album to flow, evolve, surprise, all while remaining coherent as a single artistic piece. Maybe it’s only right that the masters of crafting such massive releases should be SWANS: a band focused on the transcendence of human flesh and weakness in favour of an embrace of the godlike, the blissful, the vastness of creation. Michael Gira’s band first made such a mark in 1996. Soundtracks For The Blind contained a handful of 10-20 minute epics, a number of instrumentals and drone interludes breaking up the experience, a couple of radical reinterpretations of old SWANS tracks, some remarkably eerie found sound recordings, live recordings, even a track with pounding dancefloor beats. The band’s experimentalism, the diversity of what they created, meant it worked as an immersive album experience. Since SWANS’ return, the double album has become their standard as the band pushes post-rock song lengths to half-an-hour-plus baroque extremes. It’s an approach they’ve mastered with The Seer, To Be Kind and The Glowing Man all deservedly making numerous critics’ choice lists as well as seeing the biggest sales of SWANS long history. Currently SWANS stand as the leading, successful, exponent of the double CD: a deeply troublesome form that, in the wake of downloads, streaming and playlists may be cast aside as a physical symbol of 20th century musical excess.